Earth is under attack.

London is recovering from the Yeti invasion. Recent events have starkly demonstrated to Colonel Lethbridge-Stewart that the force behind the Yeti, the Great Intelligence, remains an active threat. To have any hope of defeating it again, he needs to know his enemy.

Forty years ago, the Great Intelligence occupied the Buddhist monastery of Det-Sen, high in the Himalayas. Now Lethbridge-Stewart plans to go to Det-Sen, in an attempt to scour the site for clues to the enemy’s nature and capabilities.

Rather to his surprise, Professor Travers, who was there as a young man, insists on coming with him.

They are not the only people interested in the Det-Sen monastery. A diabolical genius is keen to tap into the power of an ancient, dark god, and he has sent his henchmen across the world to collect the artefacts the Great Intelligence has left behind.

What is The Horror? Will it mean the end of the world – or are things much worse than that? And … what’s that sound? Can’t you hear it? That electronic sound? No, it’s still there. You can’t hear that? Really?

An unmade book, which would have been the second novel in Candy Jar’s Lethbridge-Stewart series, featuring the character who would (after a promotion) become the much-loved Brigadier in Doctor Who. I plotted it out, wrote about a third of it – 22,000 words or so – had a rough draft of the middle. It would have been a quick, fun book – both to write and (hopefully) to read. In the end, it wasn’t to be.

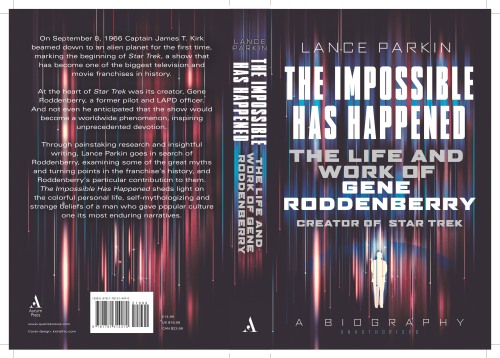

Over the summer of 2014, I was approached by series editor Andy Frankham-Allen to see if I was interested in writing for their forthcoming series. It had been a while since I’d had any fiction published, I like the character of the Brigadier, and I was in the early stages of researching my Gene Roddenberry biography, so there was room in my schedule for me to get this done, if I got a move on. It was fun to be there at the start of a new range, and I had the chance to read a draft of the first book, Forgotten Son, and offer some suggestions.

Over the course of July 2014, Andy and I exchanged a few emails. There was an idea in place for the third book before I was involved: “Given the authority to assemble a special army unit to deal with alien threats (government refuses to alert the UN at this stage). Lethbridge-Stewart is summoned by Travers to Tibet and what follows is something of a ghost/horror story featuring a haunted Det-Sen and possibly real yeti (and some alien influence). Discover something of what happened to Travers in the thirty-five years between The Abominable Snowmen and The Web of Fear, and just what did happen to his wife. (Release June 2015.)”. There was also the idea that it might involve The Beatles, or some similar characters, in a mystical retreat.

I liked that as a springboard, and I was interested in writing about the immediate aftermath of The Web of Fear. I liked the idea of starting off very soon after that story ends. I liked the idea of seeing Lethbridge-Stewart straight after his first encounter with aliens, piecing together what he knew, seeing what other people knew. Here’s a scene where he talks to a British Government official:

‘I read the report. Good work.’

Lethbridge-Stewart nodded, sensing that it meant something coming from this man, for all he looked like a colourless bureaucrat. He chanced his arm. ‘So, unlike half the top brass, you’ve read my report. Heard about anything similar?’

The man smiled, a little thinly. ‘Yes.’

Single word answers, was it?

‘Other attacks by this Intelligence?’

Lethbridge-Stewart didn’t think the man was going to answer, but he was taking his time to weigh his words before doling them out. ‘Hypothetically, Colonel, if we’d been scouted out on a few occasions by … extremely foreign visitors, which answer would be the most reassuring: that all of the scouts were acting on behalf of the same power, or that every time it was from a different power?’

‘Whether I feel reassured,’ Lethbridge-Stewart told him, ‘has very little to do with it, I’d have thought.’

‘Excellent answer.’

Lethbridge-Stewart smiled. ‘It would probably be reassuring, in a way, to think that the governments of the world knew exactly what it is we’re facing, and choose to keep things secret.’

‘And do you get the sense that is what is happening?’

‘No, sir, I do not.’

To me, it seemed like there was a really obvious thing that would have happened: London’s just been attacked by the Great Intelligence and the Yeti. For all Lethbridge-Stewart knows, they’re the only aliens out there. He would want to know all about them. Professor Travers had said he met the Yeti before in the Himalayas … so Lethbridge-Stewart would immediately want to go there and seek out evidence. Those are two fun characters, and so straight away there’s the potential for a sort of BBC budget version of the dynamic between Indiana Jones and his dad in The Last Crusade. Lethbridge-Stewart, young and fit and raring to go … and this slightly loony old man insisting he tagged along.

The old Travers in The Web of Fear is an inventor, the young Travers of The Abominable Snowmen was an explorer. Forty years is plenty of time for a career change, but I felt I needed to address that:

‘I was one of the most respected men of my day, you know? People forget that, now. There was that fool Walters, but he knew exactly what he was doing. Attack the biggest lion, don’t waste your time and energy on the cubs and the runts of the litter. There were always sceptics, but I kept proving them wrong. Until Tibet.’

‘As I say, Tibet is the reason – ’

‘Walters died in the war, you know. Oh, he wasn’t fighting. Funny story. He slipped on a paving stone and fell down a well while he was walking his dog. Doesn’t sound funny when I say it out loud.’ He laughed. ‘The dog was fine, didn’t really notice, just went home under his own steam. I always liked his dog. I was right about Tibet. That was the joke, wasn’t it? I was right about Tibet and the mechanical Yeti and the real Yeti. Didn’t matter. When I got back, my career was in ruins. Had to start again from scratch. It’s forty years later, I singlehandedly invented at least three things in every British home. You’ve got a television with a remote control?’

‘Actually, I don’t own a – ’

‘Now, unlike you, I don’t own a television, but I invented that remote control you hold every time you change channel. Made me rich. Well, rich enough to just about pay off my debts.’

There’s another quite interesting gap in Travers’ narrative between the two Yeti stories. The day after The Abominable Snowmen ended, Travers would have begun collecting up all the evidence he could of the Yeti. We know that he got a whole Yeti to London (we see it in a museum in The Web of Fear). What happened to all the other bits? Well, the way I rationalised it, Travers wouldn’t have had much money. So the bulk of what he collected would end up in storage somewhere – until he stopped paying the storage fees. And there was no way he’d kept up payments all those years, not with a World War and the collapse of the British Empire getting in the way. So the collection would have been broken up, or lost.

The obvious bad guys for this story would be a rival group trying to find the same artefacts – the events of The Web of Fear would have tipped them off, too.

I was very much in the ‘this thing writes itself’ stage, at this point, and I’d got that far in just a few minutes of thinking about the brief and what I was interested in writing about.

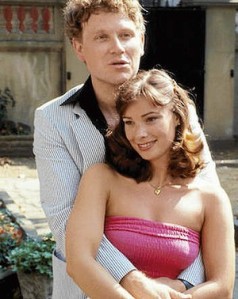

I wasn’t quite sure about the ‘voice’ of the book. The tone, the exact genre – was this a pastiche of adventure fiction, was it a light romp? A character piece? My chance to write a Terrance Dicks style novelisation? My first thought was ‘do a sort of Casino Royale thing’, where there’s this young, dynamic Lethbridge-Stewart encountering all this stuff for basically the first time. Try as I might, I couldn’t quite make Nick Courtney into Daniel Craig, and I started thinking about the late sixties, when The Web of Fear was made, and wanting to put it in that kind of setting, the Moonage and … suddenly it hit me that there was another Casino Royale option, the Peter Sellers, David Niven one. This seemed like a much better fit.

So I had the idea that the bad guys were basically Tobias Vaughn and Packer from The Invasion, but played by Peter Cook and Dudley Moore. I found that really easy to picture – the Yeti stories were made round about their Not Only, But Also phase.

I pictured Peter Cook as Drimble Wedge from Bedazzled, an aloof conceptual musician.

Here’s their first scene:

‘Ere, Wedge, are you looking in the mirror again?’

‘What does it look like?’ came the weary reply.

‘You, I hope.’

Wedge studied the face in the mirror. ‘I can’t argue with your logic, there. It does look like me. The very first thing I see is my eyes.’

‘And I can’t argue with your logic, there, boss.’

‘Is the first thing you see my eyes?’

‘I suppose, boss, that the first thing I see is your suit.’

‘It’s a nice suit.’

‘They’re nice eyes.’

‘You think so?’

‘They burn with a fierce intelligence, sir, I’ve always thought so.’

‘Burn? I’m not sure they’ve ever really burned.’

‘Not even at Pembroke?’

‘Ah, yes, the benefit of an Oxbridge education. Not even there. There, I squandered my time. My eyes smouldered, at best.’

‘You spent your time chasing birds, as I recall, sir. Lizzy, Alison, Petra. Top totty. And you netted them all.’

‘I what?’

‘Netted.’

‘I don’t recall any netting.’

‘No?’

‘None at all. Far too busy having sex with them to do any netting.’

‘Hard to see that as squandering. Time well spent, as far as I’m concerned, sir.’

‘Do you think it was my smouldering eyes that did it, Mugley? Netted the birds?’

‘Well, sir, all I can say is that I don’t have your eyes and I didn’t catch much in my net. And I had the advantages of an Oxbridge education, too.’

‘I suppose Magdalen counts as Oxbridge. It might be my eyelashes. I quite like my eyelashes.’

‘They’re super, sir. Top notch eyelashes. You’re also tall, sir. The birds love a tall man. Or, at the very least, they loathe and despise short men, such as myself, and say things like “who’s your tall friend?”, “you’re scruffy, I like your tall friend’s nice suit” and “I wouldn’t have sex with you if this was a parallel universe where everything was the exact opposite of what it is here, and all the other men had eyepatches, I’m only talking to you because I hope to catch the attention of your tall friend Peter Wedge, who I want to have sex with”.’

‘I never thought your only problem was your height, Mugley. Your height is on the list, don’t get me wrong, but I think it’s more to do with your personality. Which, frankly, is awful.’

‘I think, sir, that even if you had my personality, you would still have your cruel, sardonic face, and those cheekbones. You exude confidence, sir, if you don’t mind me saying.’

‘You don’t exude confidence, Mugley.’

‘No, sir.’

‘I don’t see you and go “there goes a man who exudes confidence”.’

‘You have the confidence enough for the both of us, sir. And quite a lot to spare.’

‘You can’t have any of my confidence, Mugley, if that’s what you’re after. Confidence doesn’t work like that. I say that with confidence. I think what it comes down to, the key difference between us, that which marks me out as a tall man who call pull totty is that I was born at the end of the age of Empire.’

‘I’m exactly the same age as you, sir.’

‘Exactly?’

‘Exactly.’

‘Exactly! The last generation, my father’s generation, if you will … well, back then a man like me with his Oxbridge education and his smouldering eyes, I’d have been a member of the ruling class. They’d have made me a minister or an ambassador, an officer of the British Empire.’

‘And now there’s no British Empire left to speak of.’

‘We were speaking of it. Just then, we were speaking about it.’

‘In the past tense, sir. And if you’re looking for gainful employment, and my understanding of this conversation was that you were, then the past tense is no use to you. There’s simply not much call for rulers of the British Empire, now.’

‘No call for it at all, no.’

‘You could rule the EEC.’

‘Not really the same, is it? I’ve got nothing against Belgians, but it’s not exactly India, is it?’

‘The one has never, ever been mistaken for the other.’

‘No it has not. They have not.’

‘There are no Belgian elephants that you can tell apart from the African ones because their ears are smaller.’

‘An excellent point that, again, points to the historical lack of confusion around the issue of whether India is Belgium.’

‘Back in the day, sir, you’re the sort of man the British Empire would have made Viceroy of India.’

‘I am. You’re right. Ironically, of course, we’re in a part of India now that was never part of India back in the days of the Raj.’

‘You’d have been a great leader of men, sir.’

‘Yes. I rather think I would.’

‘You’d have been a brilliant Hitler, sir.’

‘You think so?’

‘Oh, you’d have been a spiffing Hitler.’

‘Thank you, Mugley. Yes, I’ve thought that myself. “I’d have made a spiffing Hitler.” Those exact words. I’d have done all the things he did, I think, but avoided a lot of his key mistakes. Zigged where he zagged. It’s nice to hear someone else say that.’

‘Glad to be of service.’

‘Even coming from a revolting, insecure little gnome like yourself, it’s the sort of thing a chap likes to hear. You’d have been a rubbish Hitler, but you’d be a more than adequate Goering, you know.’

‘I like to think so.’

‘I’m going to be honest, I’d have preferred to go with the real Goering, if I was given a choice, but I wasn’t.’

‘If you want something Goered, sir, and you’ve got a choice, then go with the real Goering.’

‘I have to play the cards I was dealt. And I was dealt you, wasn’t I?’

‘You definitely were, sir.’

‘All right, then, push off, I’ve got work to do.’

He’s called Wedge in that extract, but he wouldn’t have been in the final book. The idea was this: since he’d been born, Wedge had been able to hear the Doctor Who incidental music. It gave him a sort of Spidey-Sense, warning him of danger, or if someone was a traitor. He always able to judge the mood of any situation, but it was only when he started trying to reproduce the music of the spheres that he realized that he could control people with it – make them suspicious, or deflate a serious situation.

His plan is to exploit this by creating a television event, The Horror, a sort of evil version of the All You Need is Love satellite broadcast that will be shown all around the world at the same time, that opens a portal and gives him access to the secret powers of the universe.

In order to do this, he’s kidnapped the musicians of the BBC Radiophonic Workshop, and taken them to Det-Sen, where they’re held captive. The monastery is full of hippies, groupies and other dropouts. It’s guarded by Yeti that he controls using musical cues.

He has no idea that the Great Intelligence exists, or that it’s a being with an agenda of his own.

The book would start in London, with Lethbridge-Stewart and Travers quickly flying out to Tehran, where they think the items Travers had in storage have ended up. They’d survive an encounter with the evil group, but the bad guys would escape with the artefacts.

Arriving in India, Lethbridge-Stewart and Travers would meet up with an old military colleague and a Gurkha. They are ready for a hard trek … and so are astonished to discover that Det-Sen’s just a bus ride away, now, part of the hippie trail.

Peter Wedge has been helicoptering in engineers and electronic equipment – all part of creating a state of the art recording studio and performance space, or so he claims. The monastery has become legendary for its parties, as Peter Wedge prepares the debut performance of his new album, The Horror.

There have been Yeti sightings nearby, though. Some of the partygoers have disappeared. While Travers finds the scene at Det-Sen rather agreeable, Lethbridge-Stewart is deeply suspicious.

That would be about half the book. Highlights of the second half would have included a fight in the snow between Lethbridge-Stewart and a Yeti.

A sample of the book, set on the flight to Iran, was published at the end of Forgotten Son.